RBL Passchendaele Commemoration Pin

Towards the end of 2016 I purchased a Somme 100 Lapel Pin and had to tell all about the young man that gave his life for his King and Country. The link below will take you to the story of Private G F Wood.

Passendaele 100 Pin

Following the release of the Somme 100 pin, the RBL (Royal British Legion) released the Passchendaele 100 Pin to commemorate 100 years of battle. While chatting with someone the other day I found out that one of their relatives had purchased a Passchendaele Pin. Being a bit, well a lot, on the cheeky side, I asked if she could find out the name of the person who is remembered on the card included with the pin. A day or so later I had the name of the young man.

Wakefield Family History Sharing’s Gen Blog is letting the soldier tell you about his life.

I am pleased that 100 years on, my comrades and myself are still being talked about and remembered. By having a name on a card and having a pin with a small amount of Passchendaele soil included in the poppy centre, you know that I died in time between July and November 1917. The officers told us that we were trying to take control of the ridges south of Ypres – we all called it Wipers, we had names for a lot of the towns, villages and farms. We had to, we couln’t pronounce the real name! Passchendaele was the last of these ridges. About half a mile away was a German controlled railway, it seemed that if we could take that station, vital supplies could not get through and hinder their advance. The weather was not good, mud, mud and more mud. Many men, horses and transport were continually getting stuck with not all having a happy escape. But enough of that for a while, let me tell you about me.

Oh, dear, my apologies, I am getting so excited about talking to you, that I forgot to tell you who I am – My name is Charles Frederick Jacklin, pleased to meet you.

I was born in Sutterton, Lincolnshire, in late 1894. I had three elder sisters: Louisa, and Charlotte and Ethel. Later I was to have two more sisters and a brother – Helena, George Eno and Beatrice Alice.

My parents were called Joseph and Louisa (nee Barber) who had married on December 25th 1886 in the Boston, Lincolnshire area. My dad had been married before but when he married mum, he was a widow My father was born in Butterwick, the son of another Joseph Jacklin and mum was from Wrangle, the daughter of Charles Barber. Grandad Barber was a witness at my parents marriage along with Laura Ann Cowham.

Dad’s first wife was called Rebecca Shackelton, he had married her in 1874. Sadly, she died in 1885. So, my brothers and sisters had two half siblings – Joseph, yes another one, and Henry. When Rebecca died, dad found it hard to work and bring up two children. I don’t know how he met mum, but they did and here we all are.

St Mary’s Church Sutterton

My siblings and I were all born in Sutterton. In 1901 we lived in the village, we didn’t have a real address, we just lived in the village, but we were close to everything including school and St Mary’s church.

I remember when the forms arrived for the 1911 census. We all laughed when mum and dad had to work out how many years they had been married, they’d never been asked that before. Mum was a little sad though, when dad wrote ‘none’ in the place for how many children had died. I think she was remembering someone close, who had lost a baby. Mum thought it a little hartless to ask such a question, but dad said the census people must have a reason to ask a question, as their families would also have to complete the form.

Dad, in 1911 was still working for hiself, as a builder. I was working on a farm just down the road. Two of my younger sisters were at school and we had 80 year old Charles Barber, my widowed grandad living with us. He got a pension, but I’m not sure where from. It was a good job we had a big house – 7 rooms, but we still had no real address.

If you remember, I said that we had two step siblings – well, in 1911 Henry was married and had 5 children and had lost one. Mum had thought about her grandchild when filling in their form. Henry was a dock labourer, living with his family at 29 Churchill Street, Hedon, Hull.

Life carried on as normal, well were very upset when dad died in 1912, leaving just me and my younger brother as the men in the family and grandad Barker, but you do what you have to do, don’t you. In 1914 when war was declared. All the my friends wanted to do our bit and many of us became part of the Grimsby Chums (10th Lincolnshire Regiment). All the school, sports or occupation battalions were called Pals Battalions, there were the Leeds Pals, the Bradford Pals, but we were Chums, the only Chums Battalion and we were proud of being the only one. We were part of Kitchener’s Army.

Grimsby already had its own Territorial Battalion gathering in men from Grimsby, Louth, Scunthorpe. However, there was so much enthusiasm from the men in Lincolnshire that local dignatries gained permission for us be included in new units. At first there was no uniforms but plenty of training. We trained in the grounds of the Earl of Yarborough, he had given his permission for the use of his grounds and it was quite a way outside the town and quite a way from home. We did soon get uniforms, well uniforms of sorts, they were post office uniforms that were surplus to requirements, but at least we all looked the same, well most of us did.

The Chums trained throught he winter of 1914 and by May of 1915 we had unforms, rifles and looked like proper soldiers, ready to go and fight. We marched through Cleethorpes to the park at the other end of town when we passed out.

We were now part of the 10th Lincolnshire Regiment and our training had now moved up to Ripon where we included some lads from Wakefield. Our next move was to Wiltshire. We had seen a bit of England but none of the fighting, that was until early January of the following year when we set out for France, landing at Le Havre before moving north. It was during this time that we were inspected by Lord Kitchener.

The Chums took part in the Somme battles, at La Boislle and were sent in to attack just after the explosion of the mine. Things didn’t really go to plan and when we started moving were machine-gunned by the Germans – officers and men dropped to the ground either wounded or dead. We had to retreat. We lost many good men and officers during that day and the ones that followed. We did receive replacements, these being from conscriptees as now conscription had been introduced. After the Somme we were rested.

We saw action at Vimy Ridge. Some of us stood on the top of the ridge and looked down over the plain at the enemy. We had been to Arras, took part in one of the attacks on the Hinderburg line and by 1917 were at the Ypres Salient. Here we worked repairing roads, replenished supplies and did a lot of general labouring before taking part in what was to be known as the Battle of Passchendaele. It was here that I was wounded.

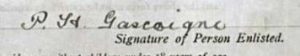

When I’d enlisted I’d gone to the nearby town of Boston and was given the service number 10/1291. I must have done something right as I was promoted to Lance Corporal.

Mendinghem Military Cemetery

I had been wounded and think I had been taken to Proven Casualty Clearing Station near Poperinge. I died of my wounds on the 25th of October 1917, and was laid to rest with as many military honours as you can have during war time, in Mendinghem Military Cemetery on the road from Poperinge to Oost-Cappel. There are over 2400 of us including 50 Germans.

My mother, as with all who were left at home, did not take the news lightly, but she carried on, she had the girls to look after and her father.

It was mum who was my next of kin and she was to get my medals – the British and Victory Medals. She also was sent £5 8s 8d in 1918, £11 11s 2d War Gratuity in December 1919 and my elder half brther Joseph received 13s 7d. It took a while really, didn’t it?

It seems that here at home I was known as Charles Frederick Jacklin, but on all my military paperwork I am Fred or Frederick. I suppose that could be confusing if someone is trying to look for me. But thankfully, that wasn’t a problem for Wakefield Family History Sharing. I appear on the village church memorial as Charles and I’m remembered with two other men from the 10th Lincolnshire, George Clarke and Hugh Keal.

The year of 1919 was a year my family would be very happy and also greatly saddened. My elder sister Louisa married John William Nix and my grandfather Charles Barber died aged 89. When he came to live with us I oftened chatted to him about the things he had seen, done and lived through.

That’s my life and death, but before I leave you I must tell you that we, the Grimsby Chums were filmed, yes, Lincolnshire lads on film. I think many of the women from Sutterton went to the pictures to see if they could see someone local or someone they knew, not sure if they did. You might like to have a look at it.

All I ask is that when you see a Passchaedale Pin or even a Somme 100 Pin, think fondly of me and Private Wood so that we shall never be forgot.