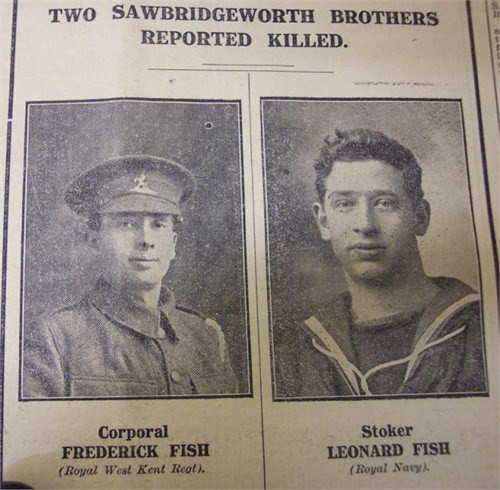

The Somme Remembered – 13th July 1916

Frederick Fish had been born to Arthur and Elizabeth Fish on 4th April 1890, Sawbridgeworth, Hertfordshire. He had been baptised on 25th May in the same year. Frederick was 10 years old in 1901 when the census enumerator recorded that the family lived on Princes Street, Ware. Arthur told he was employed as a malt maker, his eldest son, William also worked in the malt kilns – there were nine children who had their names recorded with their parents on that day in 1901.

Ten years later, Frederick, the third child to Arthur and Elizabeth, is the eldest child living with his parents and five siblings. Elizabeth, had given birth to 12 children in her 27 year marriage to Arthur and had to suffer the death of two. Frederick, like his father and brother, William, also worked in the malt kilns. Home for the family of eight was a six roomed house – 4 Elm Grove, Bishop Stortford.

Royal West Kent headstone logo

Frederick enlisted in Hertford, joining the Royal West Kent’s, and rose to become a Corporal with the serial number GS/2404. His medal card tells that he entered France on the 26th July 1915.

He must have been home on leave during the early summer of 1916 as he married Ellen Edwards in the June ¼ of 1916 before being sent to the Somme region of France.

Serre Road Cemetery No. 2 via CWGC

Again, back to Frederick’s medal card, as well as notification of three medals, it is written that on the 13 July 1916 ‘Death assumed’. He rests in Serre Road Cemeterty No 2, plot XXIX J3 along with many of his comrades.

So soon after taking her wedding vows and seeing Frederick go back to his regiment, the new Mrs Ellen Fish, was in receipt of monies due from the War Office to her husband, which was paid in two installments.

Frederick’s younger brother, Leonard born on 24th November 1893, also served during the war, he served as a K/17956, Stoker 1st Class in the Royal Navy. He was 5′ 8¾” tall with brown hair, blue eyes and a fresh complexion. After joining the Navy in 1913, Leonard served on The Pembroke II; King Edward vII; Vivid II; Royal Oak and back to the Pembroke. HMS Pembroke Drill Hall on the night of 3rd September 1917.

Bombing of 3 September 1917 via Wikipedia

Throughout its life, the Drill Hall has been used as a temporary overflow dormitory when the barrack accommodation blocks were full. In September 1917 the problem of housing the men had been further exacerbated by two unanticipated events: Firstly, the men who had been earmarked to join the battleship HMS Vanguard (1909) had been forced to remain at the barracks, after she had been sunk at Scapa Flow in July 1917. Secondly, an outbreak of ‘spotted fever’ (epidemic cerebro-spinal meningitis) in the barracks meant that the sleeping accommodation had to be increased in an effort to avoid further infection. It was the necessity of using the Drill Hall, at this time that precipitated the saddest episode in the history of this building. On Monday 3 September 1917, the Drill Hall was therefore being used as an overflow dormitory for around 900 naval ratings (either sleeping or resting upon their hammocks) when, at about 11.00pm, it suffered two hits from bombs dropped by German Gotha aeroplanes. One of the first of the First World War ‘moonlight raids’, it resulted in the loss of some 130 lives.

At 9.30 pm, 5 Gotha G.V Bombers left Gontrode in Belgium. Since the greatest loss of the bombers was during the daylight raids, a decision made to carry out a night-time attack. One of the bombers encountered engine problems and had to return to their air-base but the remaining four carried on and passed over Eastchurch (on the Isle of Sheppey) at around 11pm where they followed the River Medway towards Chatham. As this was the first night-time raid, the Medway Towns were unprepared and the whole of Chatham was illuminated with none of the anti-aircraft guns prepared for attacks.

A practice alert had been carried out earlier in the day within the town, and when the planes were finally spotted and an alert sounded, many people ignored the warning believing it to be another practice drill. 46 bombs were dropped over Gillingham and Chatham causing much damage. The drill hall suffered a direct hit. The bomb shattered the glass roof, sending dangerous shards of glass flying through the drill hall before exploding when they hit the floor. The clock upon the drill hall tower stopped at 11.12, giving the exact time the bomb exploded. The men asleep or resting inside had little chance of survival, those that were not injured from the explosion were cut to pieces by the falling pieces of glass from the roof.

Ordinary seaman Frederick W. Turpin arrived at the drill hall to offer assistance, he later recorded the scene in his notebook: “It was a gruesome task. Everywhere we found bodies in a terribly mutilated condition. Some with arms and legs missing and some headless. The gathering up of dismembered limbs turned one sick. It was a terrible affair and the old sailors, who had been in several battles, said they would rather be in ten Jutlands or Heliogolands than go through another raid such as this.”

The rescuers spent 17 hours searching through the rubble for their fellow seamen, many using their bare hands to dig through the rubble. Officers and men carried the dead bodies of comrades into buildings which had been transformed into a mortuary and the seriously wounded cases into motor ambulances which sped to the local hospital.

Mr E. Cronk, who also attended to offer assistance, stated later: “The raider dropped two bombs; one in the middle of the drill shed and one near the wall of the parade round just where the sailors were sleeping. I shall never forget that night – the lights fading and the clock stopping -we of the rescue party picking out bodies, and parts of bodies, from among glass and debris and placing them in bags, fetching out bodies in hammocks and laying them on a tarpaulin on the parade ground (you could not identify them). I carried one sailor to the sick bay who was riddled with shrapnel and had no clothes left on him. In the morning, to show that the officials could tell who was who, they had a general Pipe asking all the sailors of different messes if they could identify any of the lost; it was impossible in most cases. It was one of the most terrible nights I have ever known, the crying and the moaning of dying men who had ten minutes before been fast asleep”

Mr Gideon Gardiner described the scene of the temporary morgue within the gymnasium: “Some had never woken up; apparently the shock appeared to have stopped their hearts. They were stretched out, white, gaunt, drawn faces, with eyes nearly bolting out of their heads. Others were greatly cut up, mangled, bleeding and some were blown limb from limb”

The sailors who survived with injuries were treated on site by medics and the sick bay staff, however many of the injuries were too serious and later died at the hospital. It is estimated 90 men died whilst in their hammocks and another 40 or so seriously injured, they were not expected to live. The official total of dead after the raid was 98 however with the seriously ill in hospital, the total number rose to around 136 dead.

Woodlands Cemetery, Gillingham via CWGC

The funeral took place on Thursday 6 September with the procession consisting of 18 lorries draped with the Union Jack and each carrying 6 coffins. These 98 men were buried at Woodlands Cemetery in Gillingham with another 25 men being interred elsewhere and later burials taking place once the ratings had been identified. All the men were buried with full military honours and were followed by a procession of marching soldiers and sailors with thousands of people lining the streets.

Leonard, was one of those 98 men buried with full military honours in Woodlands Cemetery, Gillingham.

Frederick & Leonard Fish