‘Drig Lads’ who lived in the pubs of Drighlington who gave their lives in the First World War

Drighlington Pubs.

Over the years many pubs have come and gone in the small Yorkshire village of Drighlington, which is situated between Bradford and Wakefield on one road and Halifax and Leeds on another. It once thrived with several industries such as an iron works, coal mines, sweet making and mineral water making. Other industries such as woollen mills and horse hair production were also prominent before and for some time after the First World War. Farnells was a good example of an industry that changed with changing times. Situated just off the moor it produced wagon wheels in their thousands, but had to change with motorised transport coming along in the first decade of the twentieth century. The factory went on to make tennis racquets and cricket bats before finally going out of business in the 1920’s.

With good employment prospects the village pubs thrived it seems and the fact that there were still about twenty in the village at the time of the First World War showed that they could make a reasonable living and be an integral part of village life.

A map of the Cockersdale area of Drighlington in 1908 showing some of the industries that would have supported one pub, the Valley Inn.

The area around the Valley Inn in in about 1908 supported coal mines, a brass foundry, at least two mills nearby with others a little further afield and a boiler works. All no doubt with thirsty employees who would frequent the ‘Valley’ and the Cockersdale Arms, which later became the ‘Gas House Tavern’.

The two villages of Adwalton and Drighlington which make up what is now regarded as simply Drighlington also had industries scattered about their sides of the village with their own pubs. Sadly most are now gone. The Waggon and Horses, in whose outhouses I used to play with the licensee’s son as a child is now a children’s nursery the Victoria, a thriving pub in my school days with an exciting football team is now an Indian restaurant and the Painters Arms along the road has gone too.

The New Inn, closed for some time has reopened recently with a view to making it a music venue and good luck to the landlord in that venture. Communities need pubs and hopefully the remaining ones, the Railway, The Malt, the Bull, and the New Inn and Spotted Cow and the Valley, will continue to thrive, even though these days it seems to do so they have to offer food as an incentive in order to do so.

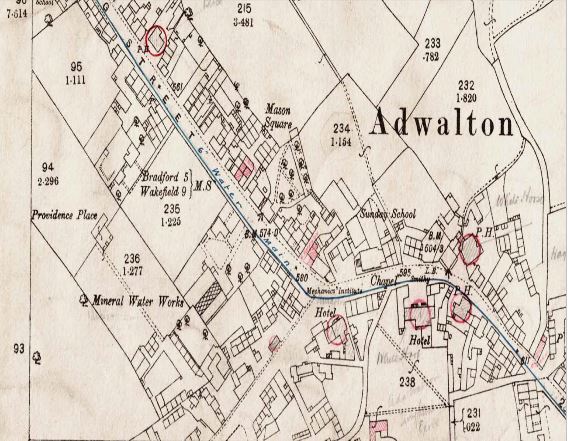

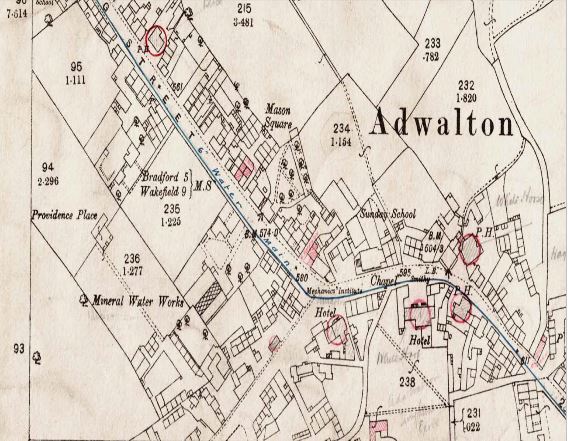

Map of Adwalton in 1908, showing at least five different pubs in the Three Road ends, King Street Area. Only the Black Bull survives, with the White Hart Hotel, the White Horse, The Waggon and Horses and the Unicorn now gone.

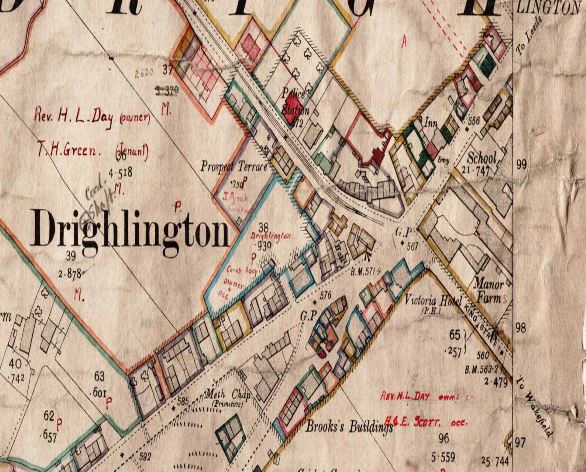

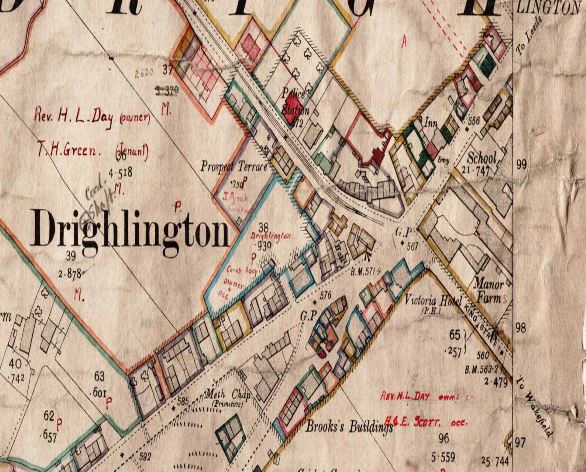

The area around the Crossroads supported at least three pubs, the Victoria and the Spotted Cow, along with the Painters Arms, along with the ‘Steam Plough Inn’ along Station Road. The Tempest Constitutional Club, which opened in 1911, made the Crossroads a good area for having plenty of pubs to choose from on an evening out. Perhaps the location of the Police Station when it was open, just along Bradford Road, was picked for its closeness to several pubs. The Gas House Tavern existed in Whitehall Road and the nicely named Steam Plough Inn was close to Brooks Buildings in Station Road next to the Drighlington Cricket Ground. Of course the Spotted Cow, infamous for its ‘talking corgi’ publicity stunt of the 1960’s is the only survivor. Perhaps the notoriety gained by the visit of the then very famous DJ and TV presenter David Jacobs gave the pub a boost to the present day!!

A map of Drighlington Cross Roads in 1908 showing the Victoria right on the Cross Roads and the Spotted Cow in Whitehall Road, opposite the old school.

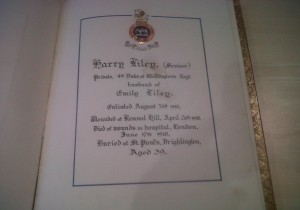

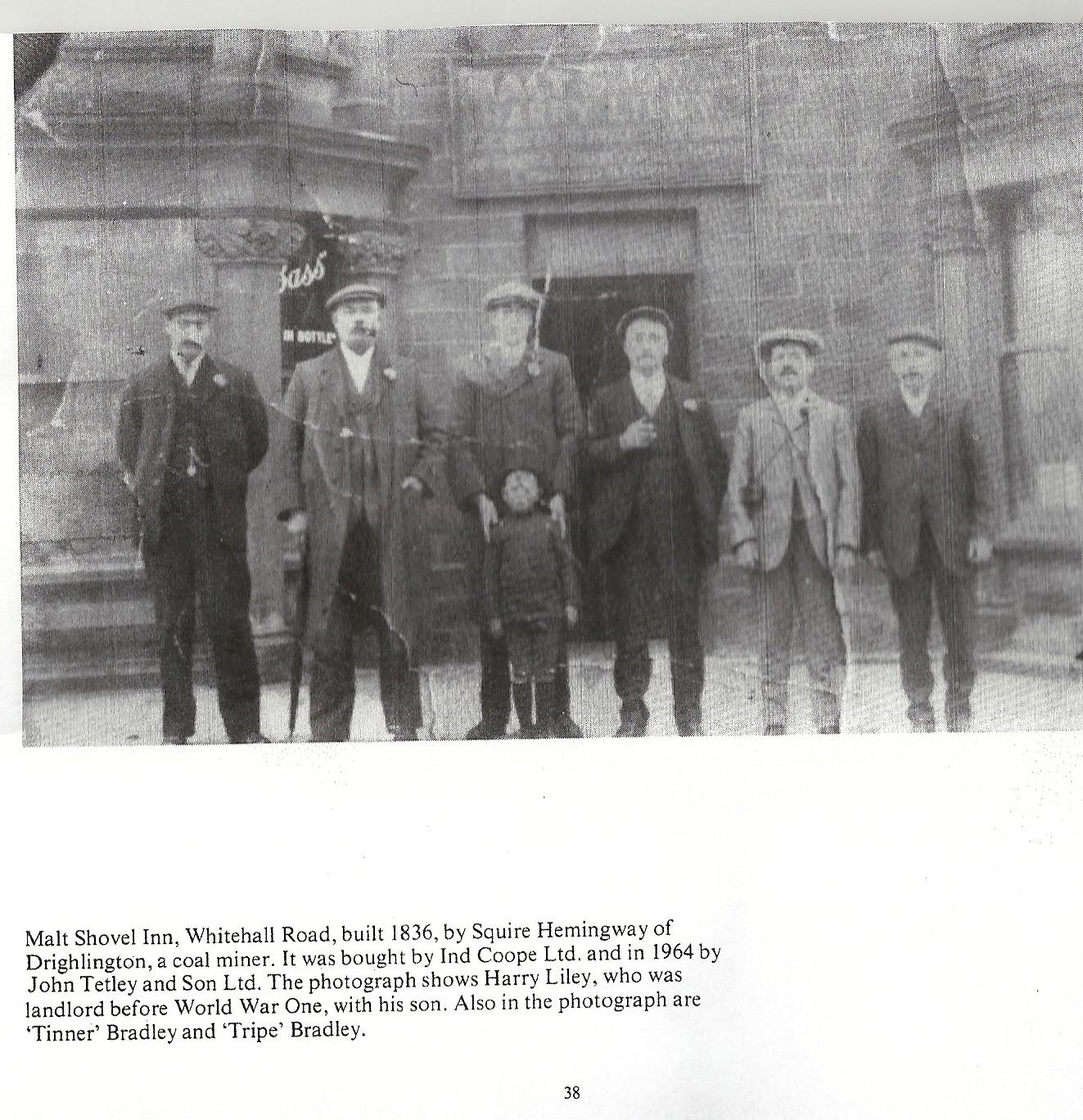

So, like many villages at the time of the First World War, pubs and clubs like Liberal and Conservative clubs formed a vital part of the community. Who knows what discussions and decisions took place in the bars of those pubs as men met to discuss the war and whether they would decide to join the colours! Certainly the landlord of the Malt Shovel had such discussions, because Harry Liley, himself the licensee joined the army on August 31st 1916. He became Private 203158 Harry Liley of the 1st/4th Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment. Harry died on June 17th 1918. He was in the Military Hospital in Endell Street in central London at the time. It seems strange as well that so many licensed premises seemed to thrive in a village which also boasted several well attended Methodist chapels like the Wesleyans, the Zion Methodists, Moorside Methodists and others.

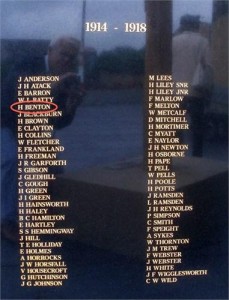

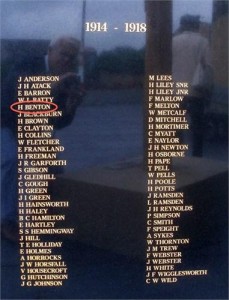

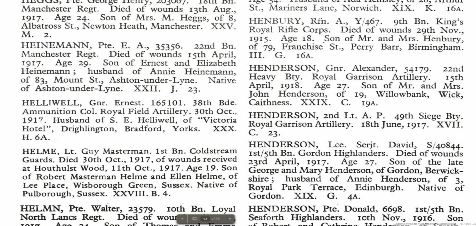

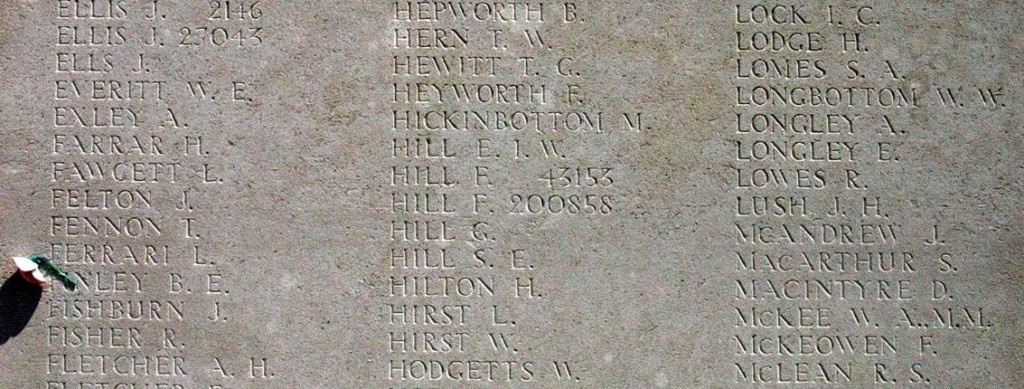

It was whilst researching the war memorial in Whitehall Road, Drighlington, that I became aware of the fact that several of the pubs in the villages of Adwalton, Drighlington and Cockersdale had actually sent their young men to fight with the army in the battlefields of Northern France and Belgium. Of the 62 names on the memorial, 4 had actually lived in pubs that were thriving at the time the war started. Two more, Helliwell and Longley, are not even named on the memorial, but they made the number of men who left the pubs they lived in, never to return, to be six.

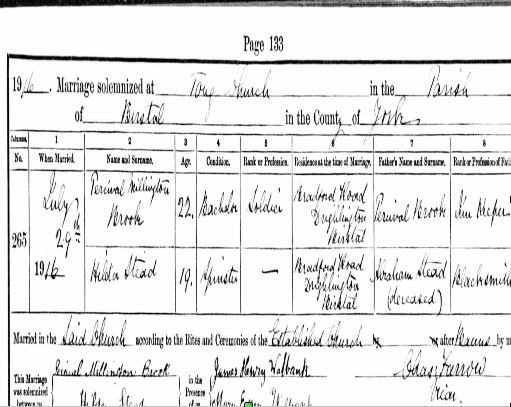

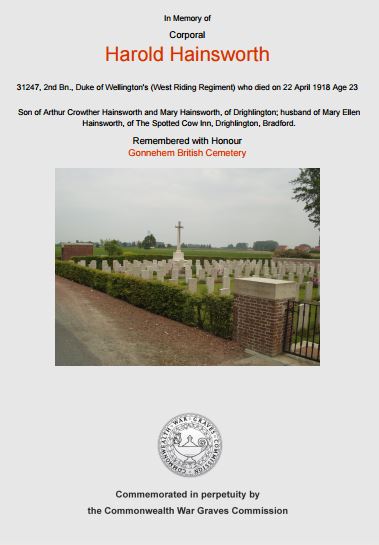

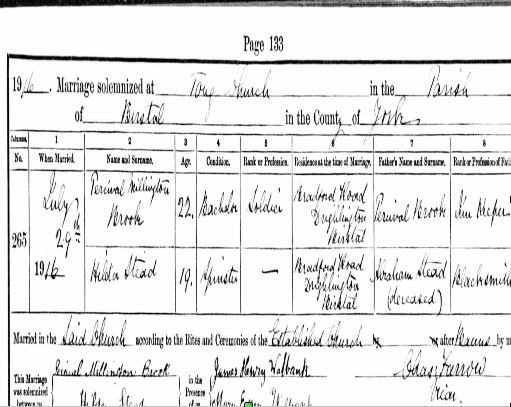

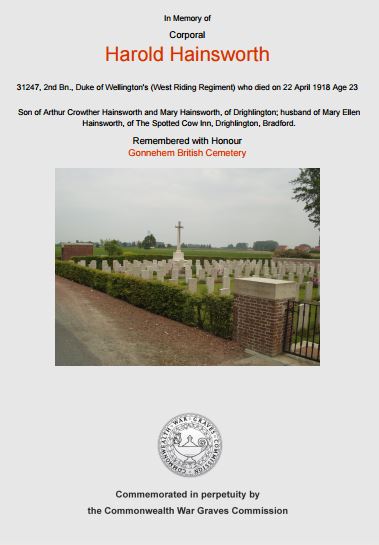

Another young man from the village also left the Steam Plough Inn, in Station Road, where his father was the landlord. Percival Millington Brooke was the son of another Percival Brooke, who had lived next door to the Steam Plough Inn in 1901, but by 1905 he had become the landlord of the very same pub! Percy Brooke survived the war but we know little of his regiment or his service. Finding his name as a soldier on his marriage certificate at Tong Church in 1916 showed that his father was an inn keeper and brought to seven the number of young men who left pubs in Drighlington to fight for King and Country. In his case he was lucky as he was to return home from the war.

The marriage certificate for Percival Brooke in 1916

Along with Liley from the Malt Shovel, Harold Hainsworth left the Spotted Cow and Ernest Helliwell was resident at the Victoria with his wife according to the Commonwealth War Grave Commission records, when he died in October 1917. His last resting place being at Etaples in France. Allen Longley was the son of the licensee of the White Hart Hotel a large many roomed hotel and public house that fronted Wakefield Road in front of the feast ground, or t’ gang as my old grandfather Joseph Wheeler used to call it. The pub was always bolstered by the horse fairs that were regularly held around the pub from the time of the granting of a fairs licence in the middle ages. Queen Elizabeth the First is reputed to have visited there on her travels, but it is highly unlikely and an urban legend only.

The pub’s main claim to fame in modern times was when it was scheduled for demolition in the 1960’s and the then owner, though not licensee as it had long since ceased trading held a Mexican shotgun standoff with police sent to evict him for some three days before finally giving up! Bernard Brennan, a native of Ireland had come to the village some years earlier and actually married my great aunt, Frances Blakey, one of four sisters of the Blakey family, my Grandma Elizabeth being one of them and Mary Anne being another, the mother of Marion Grayshon a long standing resident of the village and supporter of Moorside Methodist Church who sadly died before getting to her hundredth birthday.

Brennan, whose antics attracted coverage from the fledgling Calendar evening news show, causing a buzz in the village, is buried just around the back of the church, with my great auntie. An obelisk marks the grave.

In 1916 John George Johnson was living at the Waggon and Horses public house with his uncle, the licensee. His father had been so before that and his grandma, Mercy Johnson had also held the licence. Knowledge of John living at the pub only came to light when looking at the probate register for his death, which lists his address as that very same pub. He was to join the 1/5th Battalion of the Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment in 1916. John Johnson was to die of ‘accidental injuries’ in France on February 17th 1917. What the accidental injuries were is not actually known.

The highest honour that France gives to a soldier is the Croix de Guerre and it was this honour that was conveyed upon one Harry Benton, who was the foster son of the Tankards, the so aptly named hosts of the Railway Tavern in Whitehall Road Drighlington. When I first researched the names on the memorial it was the Railway In that I attributed Harry Benton to, but looking again at the list of pubs and the 1911 census it has become clear that the Tankards lived at the ‘Tavern’ and not the Railway Hotel, which is still open and doing good pub food despite the closure of the railway station itself in the 1960’s.

Harry Benton joined the Royal Naval Division in April of 1915 and was killed in action on a battery gun emplacement in Dunkirk in April 1917. His two colleagues on the battery were also killed and all three were afforded a funeral of honour by the French government. All three were buried together in Croxyde Military Cemetery, West Flanders. Their headstones form a group of three on their own, standing out with the badge of the Royal Naval Division on the top section.

Visiting their grave in 2014 was a poignant one for me, as was the visit to other graves of Drig lads, such as John Reynolds, an Adwalton lad like myself. John is buried in the lovely churchyard of Brevern-Uzer in Belgium, a village churchyard which made room for a handful of British casualties only, all buried not in a row but in a circle facing each other, overlooked by a marvellous village church. How funny to think that an Adwalton lad is resting there!! But then most of the men whose names are on the memorial do still reside in graves in the countries of northern Europe, excepting of course Herbert Page, who died in India almost a year after the war had ended in September 1919.

The marriage certificate for Percival Brooke in 1916

The last of the seven men to leave the pubs of Drighlington and go to war was Harold Hainsworth. He was the son of the licensee of the Spotted Cow at the time of the war, one Arthur Hainsworth. Harold left the comfortable surroundings of the pub and his wife to join the army on March 19th 1917, joining the Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment. His time before the colours was short lived and by April the following year he was killed in action, being buried in Gonneheim Cemetery Northern France.

So, those are the seven men who no doubt knew from their lives in the pubs, many of the men who had gone before them to fight for their country. Indeed , any or all of them may have been inspired to go and fight by one or more of the men whose names now sadly adorn the village memorial. However, we must never forget that as well as those whose deaths we remember on memorials, many men also seved and came back to the village to live their lives to the full.

No doubt many of these who were lucky enough to get leave to home spent evenings in the pubs of Drighlington, but one wonders if they ever tried to persuade people to join up, knowing what they did about the horrors of war and being glad to be out of it for a short period of leave. One such survivor was my own grandfather, Joseph Wheeler, originally a Birstall lad, but who came to Drighlington after the war and married one of the four Blakey sisters, daughters of the local wheelwright and undertaker. Joseph survived the horrors of the Somme faced by the Bradford Pals and came home to live in Moorside frequenting the Railway hotel two doors awy from his house on many an occasion.

Certainly it is easy to imagine that villain turned hero, Horace Osborne would have spent many hours in the Valley pub, near where he was brought up in Cockersdale, or the Cockersdale Arms. His story is a fascinating one of courage and medals, after a pre war stint with the Guards which saw him serve time in a London prison! John Willie Horsfall, another name on the memorial,who lived in Brooks buildings at the crossroads would have had his pick of the ‘Vic’, the Spotted or the Steam Plough and the Painters Arms, all within just two minutes walk of his front door.

There may well be villages in other parts of the country where pubs sent several men to fight for their country, who knows. Without detailed research into our war memorials it would be hard to tell. Certainly the pubs as community centres must have played their parts in recruiting men, as no doubt many a decision to join was made in one of the pubs as discussion of the war was made over pints of beer. However, it is the known contribution of these seven pubs in one small village that makes for a unique story and now the story of the bravery of these men can be revealed for posterity, which for the residents of Drighlington, past, present and future will hopefully be an inspiration.

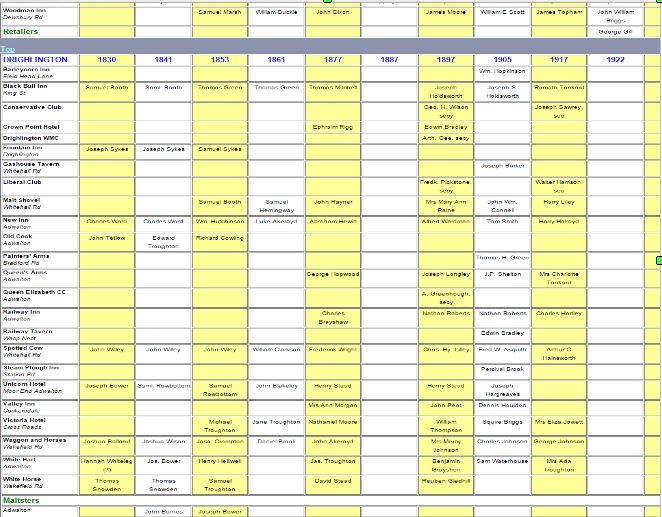

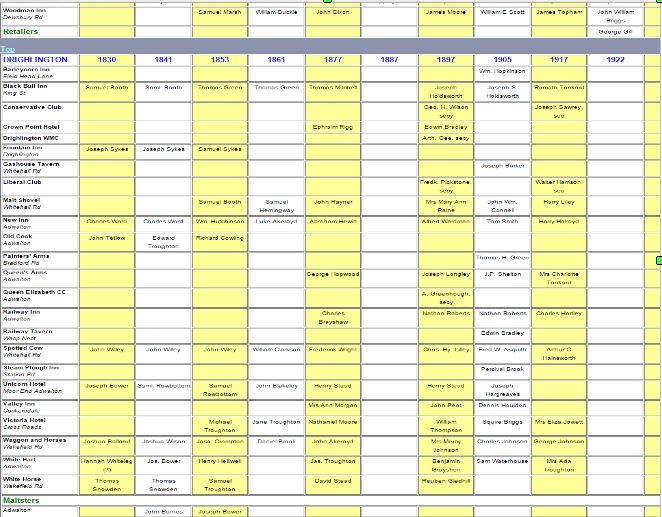

A list of the known pubs of Drighlington and their licencees (1830-1917)

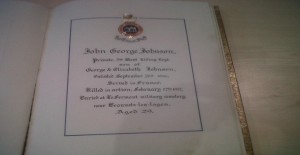

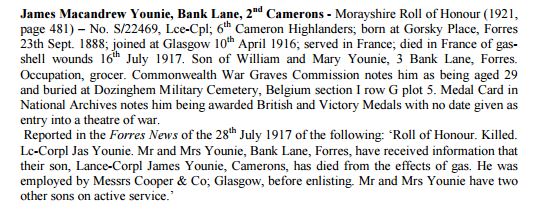

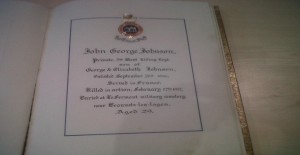

Private John George Johnson (1888-1917).

1st/5th Battalion Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding) Regiment.

The headstone for John George Johnson in Le Fermont Cemetery.

John Johnson was born in Drighlington on February 6th 1888. He was actually baptised at Drighlington Parish Church some three years later in February 1891. In that year the census showed that John’s father, George Johnson was living in Mason’s Yard, Adwalton, with his wife and John George, his 3 year old son. There were also two daughters in the family at the time. Nelley who was a babe in arms and Ellen who was 5 years old. George, who had been born in Leeds, was a cloth miller by trade. By the time of the 1901 census the family had grown to 5 children, though it is believed that Nellie had died by then. John George was working at the time as a ‘Band’ Maker, or rope maker. The Johnson family were living in Adwalton Lane by 1901.

The census of 1911 included much more detail about families than ever before. From this census we can tell that George and his wife Elizabeth actually had ten children. Eight of the children survived by 1911 and seven of them were living with their parents in Thornton’s Buildings. This was a four roomed dwelling and for five working adult people and four children to share it must have been very cramped. John George was shown as a 23 year old cloth miller at this time, like his father George.

By the time of his death in 1917 John George Johnson was actually living at the Waggon and Horses Public House in Adwalton. At the turn of the 20th century there were more than a dozen public houses in Drighlington. There were also working men’s and political clubs such as the Liberal club. Many of these establishments are long forgotten. The Steam Plough Inn, delightfully named but now gone forever from Station Road. The Unicorn no longer exists in Moorside Road, or the ‘Beesom’, though the latter still exists as a building.

Luckily there are still some pubs remaining in the village of Drighlington. Three of the seven pubs which sent men who lived in them away to war still exist in 2014. However, one other, the Waggon and Horses is now no longer a pub, though the building remains and is now a nursery.

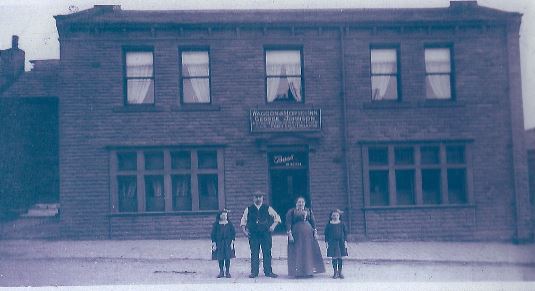

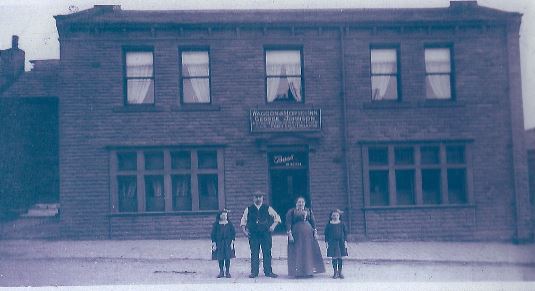

The original Waggon and Horses, with George and Elizabeth and their two daughters, probably Nelley and Ellen. The photograph is probably of about 1900.

John Johnson enlisted in the army in Bradford on September 26th 1916. He became Private 263023 Johnson of the 1/5th Battalion of the Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment. Other than this little else is known of his war service.

The entry for John Johnson in the Book of Remembrance.

John George Johnson was one of seven men to leave public houses in Drighlington six of whom did not return. His family had been landlords of the pub in the 1890’s when Mercy Johnson, John George’s grandma was the incumbent. The pub then passed to Charles Johnson and thence to his brother George. The actual link to John George and the ‘Waggon’ as it was always known, would be little known were it not for the probate registry entry for John George Johnson. It reads:

“Johnson, John George, of the Waggon and Horses inn Drighlington, Bradford a private in the West Yorkshire Regiment died February 17th 1917 in France administration (with will) Wakefield 21st June to Elizabeth Johnson, wife of George Johnson. Effects £159.17s.6d”.

The note on the probate register is at odds with the date of John’s death as posted on his headstone, but only by one day. The commonwealth war graves register shows that he actually died of accidental injuries whilst in France. No trace of what the accident was can be found as yet.

John Johnson was buried at Le Fermont Military Cemetery, Riviere in France.

Le Fermont Military Cemetery, Riviere, France.

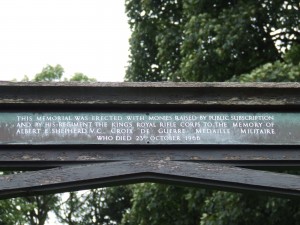

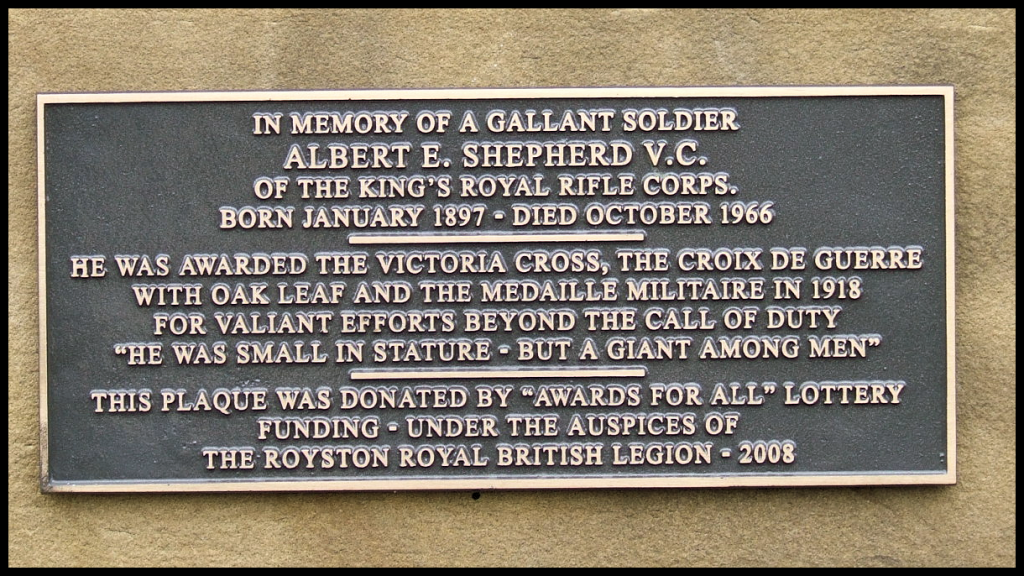

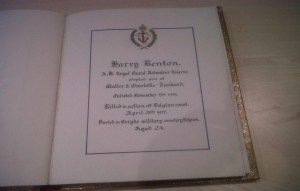

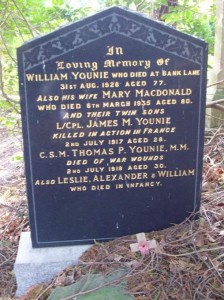

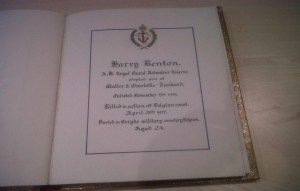

Able Seaman Harry Benton (1893-1917)

Royal Naval Division.

The gravestone of Harry Benton in Croxyde Cemetery, West Flanders.

Harry Benton was another of our soldiers who left pubs in Drighlington during the First World War to fight for King and Country. He, was not a ‘Drig’ lad but actually came to the village after he was fostered to the family who ran the Railway Tavern which was situated just off West Street near Hodgson Lane. This is not to be confused with the Railway Inn which stood and still stands opposite the old railway station in Moorside Road. The Railway Inn must have been quite a busy public house in the many years before Dr. Beeching’s cuts put paid to the railway station across the road in the mid 1960’s.

Harry Benton was actually born in Cleckheaton on June 2nd 1893. In the 1901 census Harry was shown as a 7 year old, living with his family in Gildersome. His father was Willie Benton and his mother Annie. He had a younger sister and a baby brother at the time. Willie was a hairdresser by profession.

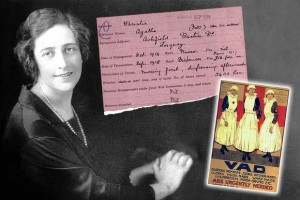

In 1901 Harry’s mother Annie died and by 1911 the family found themselves in circumstances where Harry had to be fostered out. In 1911 Harry was to be found on the census of that year living at the Railway Hotel in Drighlington. There he became the foster son of the adequately named Walter Tankard and his wife Charlotte, who were both from Drighlington and Westgate Hill themselves. Harry was 17 years old at the time and was shown to be working as a cloth finisher.

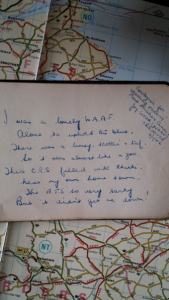

Harry Benton joined the services on April 15th 1915. His entry in the book of remembrance wrongly states that he was ‘Killed in Action off the Belgian Coast on April 26th 1917’. However, the entry is wrong in that Harry’s unit was not a sea going unit at all. Colleagues back in Drighlington writing the memorial book in the 1920’s probably saw Royal Naval Division and assumed that he died on a ship, as they wrote ‘off the coast of Belgium’. It seems that the concept of the Royal Naval Division as a land fighting force had not filtered through to the people at home even by the 1920’s. Harry was certainly on dry land when he was killed at Dunkirk in 1917.

The entry for Harry Benton in the Book of Remembrance.

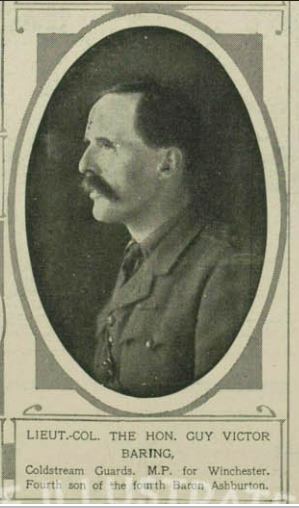

Most Drighlington men were to join local regiments such as the Leeds or Bradford Pals or the Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, but Harold Benton found himself joining the Royal Naval Division. This was a collection of battalions of largely naval personnel who were surplus to navy requirements and were kitted out as a land fighting force during the First World War. Harry though was to be posted to a naval gun unit and was sent to guard Dunkirk in case of a German rush to the coast.

He was on duty at the ‘Carnac’ battery in Dunkirk on April 26th 1917 when a German 6” naval shell burst near his gun emplacement, killing outright Sub Lieutenant Donovan and Able Seaman Harry Benton, another Able Seaman was injured and died later.

Harry Benton’s funeral was held in Belgium on April 28th 1917 and he was buried in the cemetery at Croxyde, West Flanders, Belgium. It seems that a large contingent of French, Belgian and British officers were present at the funeral and they formed a guard of honour as the cortege passed them. Prince Alexander of Teck was also noted to have attended the funeral.

This was obviously a great honour for the three British ‘sailors’ to be treated in this way. The two seaman were transported in one vehicle and the officer in another and a four mile walk was taken by the mourners to the cemetery on the nearby hillside just over the border in Belgium. The transports pulling the carriages were pulled by four horses with French soldiers riding them. A diary written at the time noted that ‘four of our machines hovered overhead’.

All in all this must have been an extraordinary way for the deaths of three servicemen to be treated, as many of their colleagues were unceremoniously buried in hastily dug graves, only to be retrieved later and placed in properly dug cemeteries.

The French must have taken the sacrifice of the three men of the Royal Naval Division to heart and they awarded them the Croix de Guerre. Able Seaman Harry Benton, late of the Railway Tavern Drighlington, went to his grave with the Croix de Guerre Second Class pinned to his uniform on top of his coffin.

A Croix de Guerre Medal like the one awarded to Drig Lad Harry Benton.

Nothing is known of how the news was to reach his foster parents in Drighlington, though one suspects that it was conveyed to them by the dreaded telegram delivered by the local telegram boy, bearing the news from the War Office and expressing deepest sympathy. By the time of his death the Tankards themselves had moved from the Railway to another pub, the Queen’s Head in Drighlington, the latter no longer exists. Thus yet another pub can be said to have mourned for one of its lost sons.

The war memorial at Drighlington with the name of Harry Benton on it.

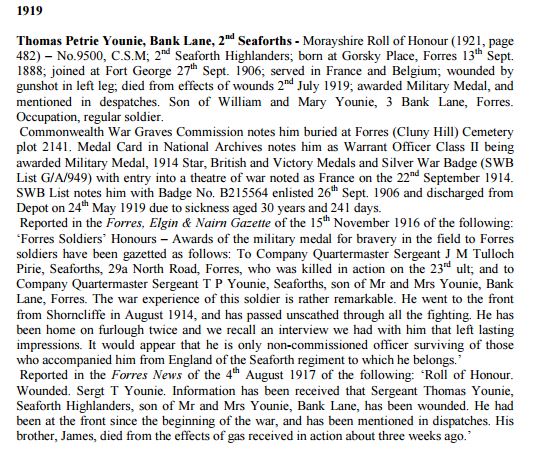

Gunner Ernest Helliwell (1893-1917).

38th Brigade Ammunition Column, Royal Field Artillery

The grave marker for Ernest Helliwell in Etaples Military Cemetery, France.

Ernest Helliwell was born in Bradford in about 1893. He was the son of Edward and Sarah Helliwell who had three other children by the time of the 1901 census recording the family’s life in East Bierley. Edward Helliwell was shown to be a railway engine driver in the census forms for that year.

By 1911 the census for that year tells us that the Helliwell family were living in Low Moor, Bradford. Edward was still working as a railway engine driver but Ernest was now in work after leaving school and had become a clerk in an office, working for a yarn merchant.

It is not known when Ernest Helliwell joined the colours, but join he did and he was posted eventually to an ammunition column working to supply the guns of the Royal Field Artillery. He was Gunner 165101. He was to die on October 30th 1917 and he was buried in Etaples Military Cemetery in France.

Little else is known about Ernest and where he lived prior to the war. However, the Commonwealth War Grave Registration documents for Ernest’s grave tell us that he was the husband of S.E. Helliwell, and that they lived, at the time of his registration with the commission, at the Victoria Hotel, which of course stood at Drighlington Crossroads for many years. The building still stands but is now an Asian restaurant.

The Victoria, where Ernest Helliwell was living with his wife prior to joining up.

Research into who ‘S.E’ Helliwell was has failed to find any record of the marriage of the Helliwells and it may well be that the couple were at the Victoria Hotel as guests for a short time and not actually living there. We cannot know the answer to that. It seems that the Helliwells reverted to their Bradford roots after the war at least. The CWGC records show that after choosing the epitaph for her husband’s grave ‘Ever Remembered’, she was recorded as living at 673 Manchester Road, Bradford.

The Probate register for Ernest Helliwell, showing his address as the Victoria Public House.

War diaries for ammunition columns are hard to trace and even when they exist it is difficult to pin down a particular death to days when mainly logistical information regarding shell numbers are recorded in the diaries.

There is somewhat of a mystery as to why Ernest was shown to be living at the Victoria Public House before he went off to war, but his albeit short stay there helps to complete an intriguing picture of no less than seven pubs which gave up their men to send them off to fight in the First World War.

Etaples Military Cemetery, France, where Ernest Helliwell is buried.

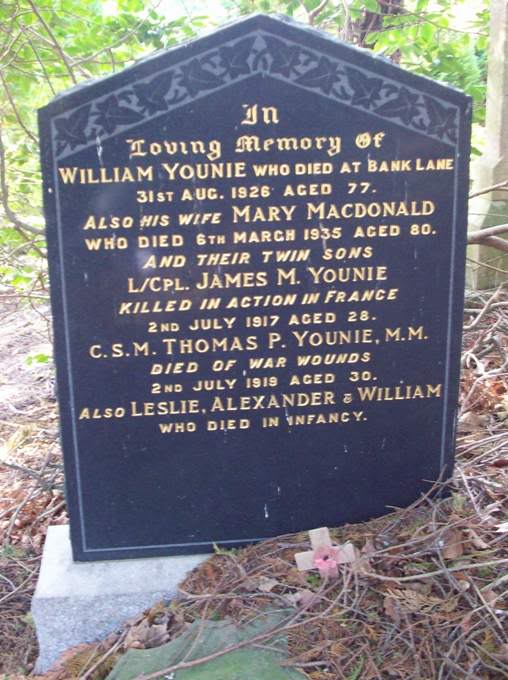

Private Allen Longley (1895-1918).

9th Battalion King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry.

Allen Longley’s name is carved on the Tyne Cot Memorial in Belgium.

Allen Longley was not a Drig Lad as such. He was born in Rothwell on May 5th 1895. His parents were Richard Allen Longley and Gertrude Maude Longley. In 1891 the census shows the Longley family at Rothwell, where Richard’s occupation was shown as a coal miner. By 1901 his occupation had changed to that of gardener.

Richard Longley obviously worked hard to grow his gardening business and by 1911 his son Allen was shown as ‘assisting in the business’ run by his father. He was 16 years old and his 17 year old sister Emily was also employed in the family business.

At some stage around the start of the First World War the Longleys took over the licence for the White Hart Hotel, the old sprawling building which once occupied a frontage along what was Adwalton Lane but was to become Wakefield Road.

The front of the old White Hart Hotel in the 1960’s.

It was from this address that Allen Longley left to go to war. Sadly, we know little of when this was as his service records do not exist. However, we do know that Allen Longley joined the 9th Battalion of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. He was to die on April 23rd 1918, at the age of 22.

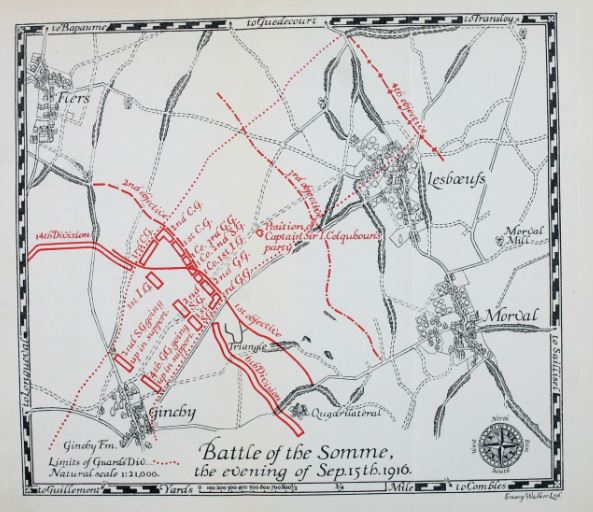

The war diary for the 9th KOYLI’s makes interesting reading around that date, and a sad story emerges of how Allen Longley probably became a victim of what is now called ‘friendly fire’. On April 20th 1918 the battalion moved to trenches at Grand Bois, near the Belgian village of Millekruis.

The war diary entry for the date of April 20th shows that even from the very beginning, the battalion, or part of it, was in trouble, but not from the enemy! It reads:

“At dark, C Company took over Forth House with two platoons from the 2nd South African Battalion. Our own artillery commenced to shell B Coy trench ( left coy) at 2pm and when the SOS was put up at 9pm bursts falling short from our own 18 pounders killed 4 and wounded 4 men”.

It seems that the battalion were unable to get the rogue battery to stop firing at them and the very next day similar entries are made in the war diary.

“In spite of remonstrations one of our gins continued to shell B coys. Trench during the early hours of the 21st, inflicting the following casualties.

One Officer Killed. 2nd Lieutenant Cundall

One officer wounded 2nd Lieutenant Woods.

12 Other ranks Killed

11 Other ranks Wounded.

The strongest protest was made against this discreditable performance and it is to be hoped that the officer of the artillery concerned will be tried by Court Martial for this carelessness.

The war diary shows that on April 23rd 1918 the 9th KOYLI’s were relieved in the trenches by the East Yorkshire regiment. The 9th went in to barracks for two days at Jasper Camp, Millekruis. There is no mention of any casualties on the day of April 23rd 1918, and it seems likely that Allen Longley was one of the ‘other ranks’ who died as a result of a carelessly aimed artillery barrage from men on his own side, dying some days later.

Allen’s body was never found, again supporting the idea that he was actually killed by shelling, albeit from his own side! His name is carved on the Tyne Cot Memorial in Belgium.

The cross at the Tyne Cot Memorial, Belgium.

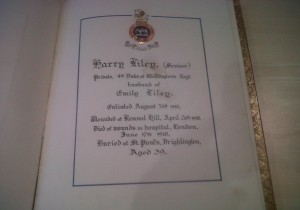

Private Henry (Harry) Liley (1878-1918)

1/4th Battalion Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment

The headstone for Harry Liley (snr) buried in Drighlington Churchyard.

There are two H. Liley’s on the Drighlington War Memorial, one notes snr and the other jnr. This may mistakenly indicate that they may have been father and son but they were not. However, it could be that the words senior and junior were added to delineate that one was 39 or 40 years of age when he died and the other was a mere 19 years of age.

There were several ‘Lileys’ in Drighlington at the turn of the 20th century, many living in the Whitehall Road area of Drighlington. In fact another member of the Liley clan who went by the name of ‘Willie’ Liley was born in Drighlington and was killed in the Great War. However, probably by virtue of the fact that he had moved to Morley by the time of his death he does not figure on the war memorial for Drighlington. His name is to be found on the Morley War Memorial.

Although the ‘H’ Liley’s on the memorial were not father and son they may well have been relatives in some way, but research would be needed to establish that. Coincidentally Harry Liley also had a son who was named ‘Willie’ but he was too young to have fought in the Great War. His full name was William Barraclough Liley, but he is entered on the 1911 census by his shortened name.

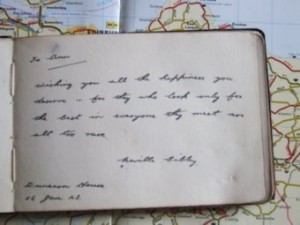

In 1911 Harry Liley was the landlord of the Malt Shovel public house in Whitehall Road, Drighlington, which is actually the nearest pub to the war memorial which now bears his name. Another pub coincidence is that when Harry married his wife Emily Bradley in1907, Emily’s address was shown as being the ‘Railway Hotel Drighlington’. However, it is unlikely that she was a landlady or related to the landlord, but possibly worked as a barmaid there. Her father was described as a stone mason on the wedding certificate. Harold Middleton Liley was 27 years old at the time and Emily was 25. Harry was a painter at the time, living in Melbourne House Drighlington. However, they were actually married at Birstall Parish Church on March 27th 1906.

Their first and only child, William, came along on December 2nd 1907, at a time when the family were living in Fieldhead Lane Birstall.

Harry was born as ‘Henry’ Middleton Liley in the summer of 1878. His father Middleton was at that time a rag merchant as well as a grocer and the family lived in a house near to the station named Melbourne House. ‘Harry’ had three sisters and two brothers in 1881. His mother had been Grace Barraclough before marrying Harry’s father. She died in 1881 so Henry was left with just his father and siblings from a young age.

In the 1901 census Henry or ‘Harry’ is to be found working away from home in Nottingham as a painter. However, by 1911 he and his wife were shown to be living at the Malt Shovel Inn, in Whitehall Road Drighlington. Harry was shown to be the publican and his wife Emily was assisting in the business. They had one servant living in the pub, the aptly named Thomas Tetley.

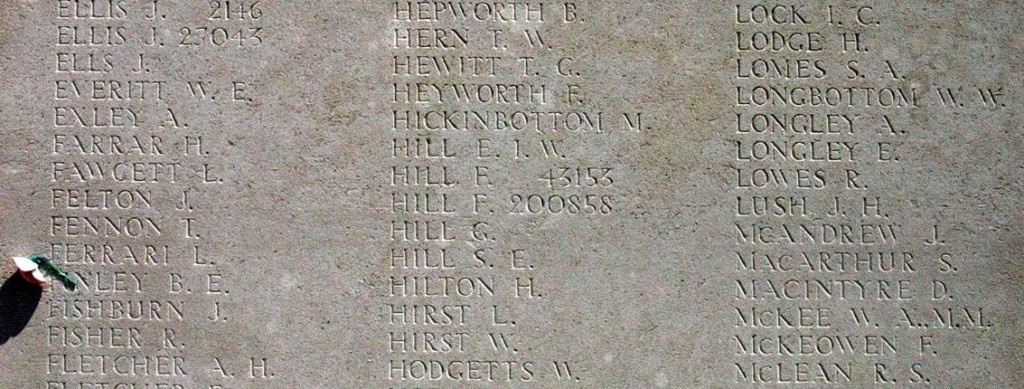

The entry for Henry Middleton Liley (Harry) in the Book of Remembrance.

According to the book of remembrance Harry Liley joined the army on August 31st 1916. He became Private 203158 Harry Liley of the 1st/4th Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment.

Harry died on June 17th 1918. He was in the Military Hospital in Endell Street in central London at the time. He had therefore been brought home from France suffering from wounds received in action. He was taken home to his family in Yorkshire and buried in Drighlington churchyard on June 21st 1918. He left the sum of £393-14s-11d to his widow Emily.

It is impossible to know how Henry Middleton Liley, otherwise known as Harry was wounded unless a member of the family comes forward in the future with family legend of it. The book of remembrance shows that he was wounded in action at the Battle of Kemmel Hill on April 26th 1918.

It is very clear that Harry felt the need to fight for his country and despite having a young child and a wife to support he left to join the colours as many Drighlington men did. One wonders how many regular attenders at his old pub the Malt Shovel actually know that a previous landlord went off to war to fight for them to be able to drink there.

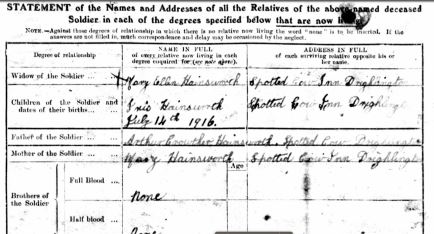

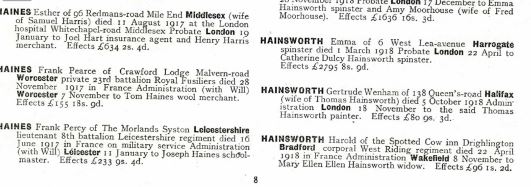

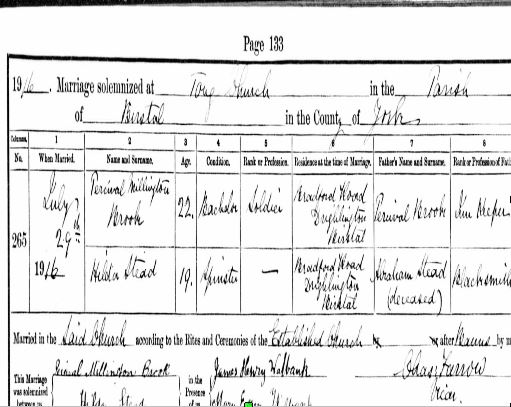

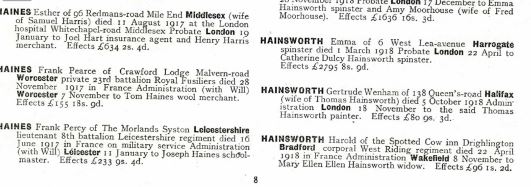

Corporal Harold Hainsworth (1895-1918).

Second Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding) Regiment.

Gonnehem British Cemetery.

Harold Hainsworth was another man living in licenced premises in Drighlington who was to lose his life in the Great War. Harold was living at the Spotted Cow Inn, opposite Drighlington Junior School, as it once was.The pub is just about one hundred yards or so from the parish church of St Paul. It is still a lively Drighlington pub today, despite the demise of many others which served the village in that era.

Harold’s father, Arthur Crowther Hainsworth was the landlord of the pub, living there with his wife, Harold’s mother, Mary Hainsworth. By the time that Harold was killed he had married Mary Ellen Tew, who had lived at number 10 Bankhouse, Pudsey. She had taken up residence at the Spotted Cow with her husband’s family. The couple married at Tong Church on July 3rd 1915.

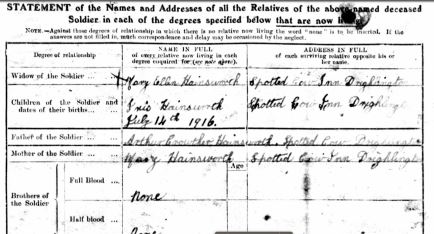

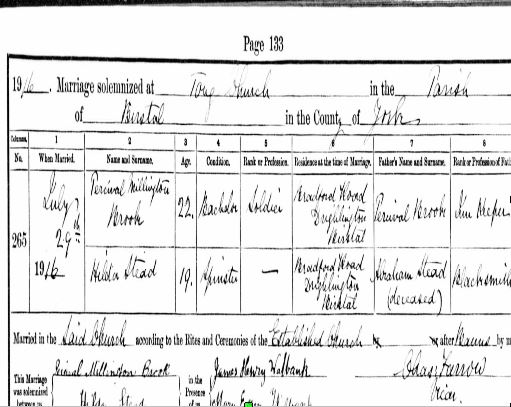

The Hainsworth’s were not actually a Drighlington family originally. Arthur Hainsworth was born in Farnley, nearby, in 1865. He married Mary Schofield, also of Farnley, on May 8th 1886. In 1887 their first son, Albert Vincent, was born but sadly he died at the age of four in 1891. Their second son, Harold, was born in 1895. Both Arthur and Mary lived until the 1940’s, losing both of their sons before their own deaths. However, Harold’s attestation papers for the army show that he had a sister, one Annie Peat. On a form asking the his wife to declare any full blood relative she cites Annie as such. However, Annie Schofield as she was before marrying was not a full blood relative, but was Mary’s daughter from a previous relationship. She is shown as living with Arthur Crowther Hainsworth and Mary in the census of 1901.

Arthur seems to have had differing jobs in his youth before finally becoming a publican. In 1891 he was working as a blast furnace stoker and by 1901 he was working on the roads a labourer, breaking stones.

By the time of the 1911 census he was shown to be a publican, living in Bankhouse Lane, Pudsey. It is likely that he ran a pub there and the Bankhouse Inn, still in use today, may well have been his first public house.

By the time of Harold Hainsworth’s death in 1918 however, the Hainsworth family had moved to Drighlington and Arthur had become the licensee of the Spotted Cow in Drighlington.

The Spotted Cow Inn.

In 1911 Harold Hainsworth was working as a garden labourer, whilst his father ran the pub in Bankhouse Lane. He was sixteen years old at the time but by 1915 at the age of twenty he was to marry Mary Ellen Tew, who had lived at 10 Bank House Pudsey, no doubt not far from the public house his family owned. By this time Harold had become a fettler in the local mills.

War broke out on August 4th 1914, but it was not until 1915 that Harold Hainsworth enlisted in the army. Surprisingly it was to be another two years before he was called to the colours. Luckily his attestation papers survived the blitz of the Second World War and from these papers we can see his postings and obtain some knowledge of his life in the army. Unfortunately the papers of many soldiers from the First World War were destroyed by Luftwaffe raids on London in the Second World conflict.

On December 8th 1915 Harold Hainsworth travelled to Halifax and signed his enlistment forms to join the Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment. It may be that the enthusiasm shown in the area for joining regiments such as the Leeds Pals and the Bradford Pals inspired him to eventually join the colours himself. It was to be more than a year before Harold was actually mobilised on March 19th 1917. The attrition rate amongst young soldiers in 1916 obviously brought about the need to mobilize those who had already been recruited but not yet called up.

Harold and Mary were to have one child, Iris, who was born on July 14th 1916. Whether the recruiting officer at the time spared Harold from joining his regiment because his wife was pregnant is doubtful, but certainly a possibility which explains the long time between December 1915 and March 1917. Certainly, other men were being called up in their thousands and Harold was not in a reserved occupation, showing on his forms that he was now a ‘Fettler and Grinder’ at a mill making gun cloth.

The service record for Harold Hainsworth.

From his medical notes in his attestation forms we know that Harold Hainsworth was 5’6” tall. Not a very tall man but bearing in mind many of the recruits of the time were much smaller than modern day young men of the same age he was probably of average height for the time. The existence of ‘Bantam’ regiments where recruits had to be less than 5’3” tall to join bears testament to the fact that many men were of small stature, especially in the mining areas of the industrial north. His medical notes show that his teeth were ‘decayed’ and that his joining up was subject to medical treatment, so this may well have been the reason for the delay in him actually being mobilised.

Harold was medically examined for joining up in March of 1917. His weight was shown as 131 pounds. He was then 22 years old. We even know that his chest measurement was 34 ½ inches and that his general physique was ‘good’.

It is not known where Harold received his training in full, although we can tell from his records that by August of 1917 he was at Chirton Camp in South Shields. On August 15th 1917 he was shown as ‘Absent Without Leave’ from the evening of August 15th until 6-30 am the next day. His punishment for this was admonishment and the forfeit of one day’s pay.

Only a few days later Harold embarked from Folkestone for Boulogne on August 23rd 1917. He was posted to the 10th Battalion of the ‘Dukes’ at that time but on August 31st he was posted to the 2nd Battalion, with whom he was to remain for the rest of his service.

There is one incident of note on Harold’s file from this time, this being an injury to his scalp on October 21st 1917. Such were the sensibilities about soldiers injuring themselves intentionally in order to be invalided home (colloquially known as getting a ‘Blighty One’ when wounded), that all injuries had to be investigated and witnesses sought. On October 27th 1917 Harold Hainsowrth was involved in an injury that needed such an investigation. He was an acting Lance Corporal by this time, but unpaid it seems as the status of being paid for the rank was not afforded him until Novembr 7th 1917. On the same day he was appointed Acting Corporal, no doubt to cover for losses in that rank in the regiment.

Harold sustained a injury to his scalp on October 27th 1917 which necessitated him being hospitalised.

“Statement of witness as to the circumstances under which L/Cpl No. 31247 H. Hainsworth recived an injury to his head”.

1st Witness. J.C. Marshall 2ndBattalion Duke of Wellington’s Regt. States.

“ On 27th Oct. 1917 I was in charge of No 3 Platoon, No 1 Coy. The platoon was doing physical training and L/Cpl. H. Hainsworth was present. The order was given for the men to double around a wagon which was standing near and in doubling round this L/Cpl Hainsworth struck his head against an iron pipe which was projecting from the wagon”.

2nd. Lt. J. C. Marshall.

Lieutenant Marshall’s statement was one of three taken to ensure that Harold had not actually inflicted the wound upon himself in order to avoid duties at the front. It was an unfortunate and unlucky incident, and came only one day after Harold was reprimanded because he had a dirty mess tin upon being inspected by his officers on October 26th 1917.

Though the accident happened on October 27th 1917 it seems that Harold did not receive hospital treatment for it until November 6th, when his file shows that he was taken to hospital. It may be that the scalp wound had become infected, as a further entry for November 11th 1917 shows that he was then taken to a casualty clearing station. He was to stay there for some days and finlly rejoined his unit on November 22nd 1917. The infection, if that is what it was, may well have caused the next admission to hospital for Harold in January of 1918. The initials P.U.O. appear in his file, diagnosed by the 10th Field Ambulance Unit on January 26th 1918.

The initials PUO stood for ‘Pyrexia of Unknown Origin’, which was a medical term usually applied to a diagnosis of Trench Fever. He returned to the 2nd Battalion on February 7th 1918, whereupon he was immediately sent to ‘Bomb School’. Corporal Hainsworth remained at the bomb school for about a month, returning to his unit on March 18th 1918.

He was to be with them for just one more month or so, as on April 23rd 1918 he was killed in action. He is buried in Gonneheim Cemetery in Northern France, a village which the Germans were advancing on in April 1918, reaching to within 3 miles of the village. It was an action in what was known as the Battle of Bethune. Harold’s medal record simply states K.A.

When the army records office asked Mary Ellen Hainsworth to fill in a form regarding the nearest relatives to Harold in 1919 the family were still living at the Spotted Cow Inn, but it is not known what happened to them after this time. The form was to sort out who would receive the plaque and scroll given to relatives of fallen soldiers. Mary Ellen, his wife, was already receiving a separation allowance of a paltry 19/6d and this would have been included in the eventual pension calculation she received. It took until 1921 for the family to receive Harold’s Victory medal and the plaque and scroll.

Luckily Harold had filled in the ‘Will Page’ which was included in the paybook of all soldiers at the front at the time. This meant that there were no legal difficulties in Mary Ellen getting what money he did leave. This totalled £96-1s-2d.

On August 28th 1918 the Army Records Office at York wrote to Mary Ellen at the Spotted Cow, asking her to send a receipt in exchange for receiving the effects of her late husband. All that Harold Hainsworth’s wife received from the front were a note book, a photo, and some cards.

The probate record for Harold Hainwsorth.

The name of H. Hainsworth, namely Corporal 31247 Harold Hainsworth is featured on the recently refurbished Drighlington War Memorial, in Whitehall Road, Drighlington.

The Commonwealth War Grave Commission Certififcate for Harold Hainsworth.

Percival Millington Brook

The Steam Plough Inn.

The marriage certificate of Percy Brook, son of the landlord of the Steam Plough Inn.

Without the discovery of the marriage certificate for Percy Brook and Hilda Stead little would be known about Percy Millington Brook. However, the fact thathis occupation is listed as a soldierupon the certificatetells us that here was another Drig Lad who went to war from his home in a pub in the village.

Percival Millington Brook was the son of Percival and Mary Ann Brook. In 1901 the two were living in Brooks Buildings, a substantial row of houses which stood until late into the 20th century at the beginning of Station Road, on the left before the cricket ground. At that time the Brooks lived right next door to the Steam Plough Inn, in Station Road. The landlord of the pub at that time was Sam Theaker. By 1905, however, Percival Brook senior had taken over the licence of the pub. The 1911 census shows that Percival Brook was now a ‘Beer House Keeper’. This was a change from his job as a weaving overlooker as he was in 1901. Percival (snr) was a Drighlington born man but his wife Mary Ann was from Cleckheaton. In 1911 the Brooks had six children living with them, sadly, one of their children had died by then. Percival Millington Brook was 16 years old in 1911 and was a warehouse boy.

Unfortunately at this juncture it has been impossible to trace which regiment Percy Millington Brook joined when he went to war. It is clear that he was serving as a soldier by July 1916 and he also survived the war to return no doubt to his native Drighlington. Perhaps family historians of the future will be able to fill in the gaps of our knowledge about the men such as Percy Brook who went away but actually came back from the war.

As it is is, the story of Percival Millington Brook, sparse in detail as it is, completes an interesting tale for the village of Drighlington. A small village sent seven of its men from pubs around the village to fight in the Great War. Only one of them came back!

Brooks Buildings in Station Road Drighlington, pictured in the 1960’s.

Epilogue.

The story of these seven men and their pubs will be sent to all of the existing pubs in Drighlington, as well as the local library. One would hope that the present landlords and customers will enjoy reading of men who lived and worked in their pubs one hundred years ago. Who knows, their stories may inspire the landlords to drink a glass of beer to the men on the date of their deaths, in a special evening to remember them. That would be nice. Sadly there are only two of the pubs here mentioned still trading, the Spotted and the Malt, otherwise a good pub crawl between the pubs might have been a good idea.

However, there are still enough pubs in the village for people to visit and think that they are standing drinking in a bar that was undoubtedly visited by many of our soldiers whilst waiting to go or at home on leave. Again, a glass or two might be raised to them, whether in the Bull or the Valley or the Malt or the Spotted.

One hopes that the present landlords might get together with their regulars and find a way to honour these men for one night a year, at least for the next four years or so whilst the country commemorates the losses of the First World War. That would be a nice thing.

Perhaps someone will organise a Battlefield Tour to visit some of the graves of our village fallen. It’s a long way to travel even to get to the channel ports, but I can assure you that any visit made will be poignant and and facsinating to do. I hope that some people reading this might feel inspired to go and visit the places mentioned for themselves.

Villages and communities need pubs. They provide a community spirit and a place to go for people to meet. No doubt that sense of needing somewhere was much more acute in the years between 1914 and 1918. So, if you are not reading this in one of the pubs then make a point of visiting one of the Drighlington pubs in the near future and raise a glass to these men, but not only these, to the 62 men on the village memorial and to the few who are not, but still gave their lives, and also to those who served but came home wounded or damaged by the horrors they had seen. Like many of you reading this they will always be Drig lads through and through, like myself!

Guest Blogger………Philip L. Wheeler

Thank you to Brian Furniss for helping with background information and photographs of the pubs from his great archive of Drighlington photographs.

Additioal information by Donald Briggs :-

In the above guest blog by Philip L. Wheeler I believe some of the information regarding Ernest Helliwell is incorrect. My research has revealed the following: – Ernest Helliwell – Gunner 165101 Born 1884 in Bradford. Son of William Helliwell and Jane (nee Davenport) who had four other children. William was a Joiner (Journeyman).Ernest married Sarah Elizabeth Ibbitson on 25th September 1911 at Bradford Register Office. At the time of their marriage Ernest was living at 18 Herbert Street, Bradford working as a Telephone Operator and Sarah was a Cloth Weaver living at 673 Manchester Road, Bradford. Their daughter Mary was born in 1912.

Like this:

Like Loading...